The fried history of an export we re-imported.

If you watch a lot of cooking shows, there’s a word that keeps recurring in modern culinary discourse: elevate. It’s thrown around casually, as in, “I made a chicken sandwich, but I made an elevated chicken sandwich.”

My understanding is that this is a caveat to the basic piece of kitchen wisdom that your recipe will never be better than your ingredients. Your apple pie will only be as good as your apples, your croissants will only be as good as your butter, and the quality of your bouillabaisse is limited by your ability to source high-quality seafood.

The caveat is that a recipe can still provide the palate a context and counterpoint for the flavors and textures of ingredients that can elevate their positive aspects. The apple pie may never be better than its apples, but the right mixture of sugar, salt and spices can help you appreciate the apple more than you would its raw state.

This, my friends, is elevated zucchini.

The patties are impossibly light, with a crisp exterior and a rich interior; the flesh of the zucchini is firm but tender, almost like an artichoke heart.

Fried zucchini is an international favorite–the Greeks have kolokithokeftedes, a fried zucchini tapa; the Spanish have their own tapa, zarangollo, made from zucchini and onions that are fried or sauteed together, then mixed with egg; and the Italians fry both the blossoms (often stuffed with cheese) and the flesh into fritters substantially like these.

Have you ever thought it odd that zucchini has an Italian name when we’re all told that squash is native to the Americas? It’s a little odd, when you think about it, that the most common kinds of summer squash we encounter are crookneck, straight-neck, patty pan, and zucchini. It’s like being introduced to four brothers named Matthew, Mark, Luke, and Fabrizio.

First, we should understand the distinction between summer squash (like zucchini) and winter squash (like pumpkins). Summer squash has small seeds and soft skin, while winter squash has a harder shell and large seeds. Both grow in the summer, but winter squash got its name because it can be stored until winter.

The name zucchini is derived from the Italian word zucca, which means squash, and the suffix -ini, one of the various Italian suffixes meaning little. The name is a clue as to how you should pick a zucchini, if you have the choice. The smaller a zucchini is, the more tender, fleshy, and sweet it is; as the zucchini grows larger, it becomes watery and bland.

There aren’t particularly old recipes for zucchini, however, because the hybrid summer squash named zucchini didn’t exist until the late 19th century. Summer squash varieties (like the crookneck squash or pattypan squash) are native to North America; seeds have been found in dig sites that date to at least 4,000 B.C. While Roman cookbooks include descriptions of winter squash, it’s likely that summer squash was something Columbus brought to Europe.

One interesting wrinkle is that the word squash itself was a corruption of the Narragansett Native American word for the plant, askutasquash, which meant “eaten green or raw.” While many Native Americans did eat the squash raw, they were also enjoyed roasted or mashed, and colonists adopted the cooked versions. And the method we use to make zucchini patties existed in the 19th century, used to make fritters out of leftover mashed summer squash.

For example, consider the following pre-zucchini recipes for squash from the September 13, 1877 edition of the Monroeville (Indiana) Democrat:

|

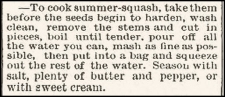

— To cook summer-squash, take them before the seeds begin to harden, wash clean, remove the stems and cut in pieces, boil until tender. Pour off all the water you can, mash as fine as possible, then put into a bag and squeeze out the rest of the water. Season with salt, plenty of butter and pepper, or with sweet cream.

|

|

|

–To make squash fritters, take a pint–more or less–from the dinner-table, one egg and two tablespoonfuls of flour. Fry on the griddle for breakfast.

|

Given our national love of all things fried, it probably comes as no surprise that the fritters were popular. Here’s a recipe from the August 23, 1900 edition of the Acton Concord (Massachusetts) Enterprise that does away with the pretense of mashed squash as the intended result:

|

Recipes From Many Sources and of Acknowledged Worth

Squash Fritters Peel two good-sized summer squash, cut in small pieces, place in a steamer and cook until done; then mash well, taking all the seeds from them. To this add two tablespoonfuls of fresh milk and a tablespoonful of flour, a teaspoonful of salt, and two eggs beaten thoroughly, a teaspoonful of yeast powder, mix well, then fry in boiling lard until brown. |

Over the decades, as we became more comfortable with zucchini, it started to take the place of the other squash varieties in our fried preparations. Here’s a version from the August 10, 1967 edition of the Muscatine (Iowa) Journal:

|

“One of My Favorite Recipes Is…

Zucchini Patties 1 large or 2 medium size Zucchini; peel and slice in small pieces — add 1 medium size onion chopped. Cook in salt water until tender. Drain all excess water–then add about 1/2 cup cracker crumbs–1 egg–salt and pepper. Drop by spoonful in hot shortening until brown on both sides.

Mrs. Edward Bartkus

Lake Park Blvd. Wouldn’t you like to share one of your “Favorite Recipes” with the other readers who have so generously shared their recipes with you? Just mail to Favorite Recipe Editor, Muscatine Journal. |

Notice that the recipes above call for boiling or steaming the squash, while the recipe we use requires salting the squash. That has to do with a better understanding of the mechanics of plant cell structures than our culinary predecessors had.

When you have a raw piece of squash, much of the water is contained in cells. The heat of cooking damages the cells; that means water leaking into our hot oil, which means splattering, and water in our zucchini patties–which means a soggy patty. We need to remove water from those cell-balloons before we fry them.

So we have a few options. We could cook the zucchini in advance; that would burst the cells, which would let us squeeze out the water and have a crisp patty. That’s how steaming and boiling works.

A second, similar, option would be to freeze, then thaw the zucchini, which would have about the same effect as blanching, rupturing cells and emptying water.

But another way is to salt the zucchini. Our old friend osmosis will kick in–negative water ions will be drawn to the positive salt ions, passing through the cell walls. (Click for a digression on salting vegetables and osmosis, if you care.)

| Happy Fun Cell Membrane Destruction Corner

Salting may or may not damage the cell, depending on how long you leave the salt and how much salt there is. In this recipe, we just plain old don’t care if the cell membranes are damaged or not. We’re going to destroy them in cooking anyway, we just want the water removed. But there are times when we do care, such as when we’re making a cucumber salad, and we want it not to be watery but still to have some of the crisp bite of the cucumber. Too much salt or too much time can result in damaged cells. In plain language, the water rushes out of the cell because it’s attracted to the salt; the salt water is drawn back into the cell in an attempt to balance the pressure; and the salt in the cell draws more water in than the cell is intended to hold, and the membrane bursts. So for this recipe, it doesn’t matter how much salt you use, but if a recipe specifies an amount of salt or a time, you should either follow the directions or keep an eye on your vegetable to look for the osmotic sweet spot, where it’s not as crisp but somehow still crunchy. |

The result of the process is an achievement that’s almost too good to describe as vegetable-based. The patties are impossibly light, with a crisp exterior and a rich interior; the flesh of the zucchini is firm but tender, almost like an artichoke heart. The flavor profile is unrepentantly Italian, the Parmesan and oregano taking on a range of flavors depending on whether they’re in the crust or the patty itself.

A note from my Julie who makes these with tzatziki, Greek style–she says: “I think you should substitute parsley for the thyme. If you look at the ingredients, parsley is a much better fit.” (I’m sure it’s fantastic either way.) She also says you can substitute chickpea flour if you want a gluten-free version, but that the batter was a bit dryer and she used two eggs.

Some recipes reward only seasoned palates; some are for everyone. This is a recipe for everyone. It’s a rare thing, to watch children fight over the last of the zucchini, but I assure you, that will happen if you make these.

From Yesterdish’s recipe box.

Yesterdish’s Zucchini Patties

1-1/2 cup grated raw zucchini (about 3 zucchini)

2 Tbsp. minced onion

1/4 cup Parmigiano, grated

1/4 tsp. oregano

1 large egg

1/4 cup A/P flour

1/2 tsp. kosher salt

3 Tbsp. minced chives

1 Tbsp. cornstarch

black pepper

oil for frying

- Grate the zucchini–place in colander, salt; toss and rest for at least 10 minutes.

(You must drain it). - After you squeeze as much liquid as you can from the zucchini, place it in a large bowl.

- Mix in all the other ingredients–adjust salt and pepper to taste–you should have a thick mixture.

- Spoon the batter (1/4 cup) into heated oil–flatten a bit, cook 3 minutes per side–transfer to a paper-lined plate–season with salt if needed. Serve!