The bread that defined travel, convenience, government folly, and in the process, American progress.

The square white sandwich loaf might seem as American as apple pie. But like many American foods–like, say, apple pie–the story really starts elsewhere.

When you think of iconic French bread, you think of the baguette, the rounded loaf baked to produce a delicious crust. But there are things a baguette doesn’t do so well.

For example, it’s not much help in making bread crumbs. Canapes made with a baguette end up more like bruschetta. And an egg salad sandwich on a baguette usually ends up with the contents squeezed out the back like a tube of toothpaste while you bite through other end.

For all of these applications, and more, the French developed a solution in the 18th century: the pain de mie.

The greatest thing leading up to sliced bread.

Mie is the French word for the interior of a loaf of bread–what they call the crumb, in baking circles. The goal was to make a loaf of bread with a tight, compressed, moist interior that could be isolated for canapes. To do that, they started baking bread in square pans with lids; sealing in the steam made a finer crumb and kept the bread soft while ensuring flat edges that could be quickly removed with a knife.

So the technical hurdles of baking a soft white loaf had been cleared by the late 19th century, when George Pullman was trying to solve an equally mechanical problem.

Pullman was born in the Western part of New York State on March 3, 1831, and trained as an engineer. Sometime in the 1850s, he was sleeping in his seat on an overnight train when he had the idea for a more comfortable train car–a train with sleeping berths for every passenger. He founded the Pullman Palace Car Company in 1862. In 1865, he “generously” arranged to have the body of President Lincoln transported from Washington, D.C. to Springfield, Illinois in a sleeper car. After that, his cars garnered more and more attention, and more people wanted to travel by Pullman sleeper car.

The cars were luxurious, and included dining facilities, which ultimately posed a problem. Like most rail cars, Pullman cars were just over 44 feet long and just over 10 feet wide. In that space, up to 11 men would be expected to prepare made-to-order meals for 220 passengers, on demand, day and night. (The photo is from a 1970s-era car; the length of cars shifted from time to time but the width remained the same.)

Add in ovens, stoves, iceboxes and the like, and soon the galley car (so called after the word for Navy kitchens) hardly had room for food. And that was the mechanical problem Pullman faced: how do you fit as much food as possible into a small space? Especially the one food that was likely to be requested at every single meal: bread.

You didn’t need to be an engineer to figure out the geometric solution: make bread in a shape that can be stacked without empty space between it.

Through trial and error, the company realized that three square pain de mie loaves could fit in the space occupied by two traditional round-top loaves. Soon, Pullman galley cars were stocked with loaf after square loaf, and to this day, the baking industry refers to a 13-by-four-by-four loaf of white bread as a Pullman loaf.

Pullman loaves quickly became associated with higher-class dining, even among those who didn’t go near trains. Why? I’d guess it’s partially that the Pullman Palace cars were how you traveled if you could afford to; partially because the loaves would be used to make canapes and sandwiches for tea, a holdover of their French origin; and partially because something about the stark geometry of the slices appealed to the progressive spirit of the late 19th century.

Whatever the reason, there’s no question that by the early 20th century, Pullman loves were being sold at double the cost of regular loaves in bakeries around the country, while advertisements boasted that high-class hotels preferred them.

(To be fair, Pullman loaves can be about one and a half times the volume of their predecessors, but it’s hard to measure, given the possible varieties of bread involved.)

Over time, the popularity of the Pullman loaf would be the spark that would set off the proliferation of the white sandwich loaf in bakeries and grocers nationwide. But while the Pullman loaf was the spark, the fuel was provided by Otto Frederick Rohwedder.

Rohwedder was born in Des Moines, Iowa in 1880. He became a jeweler and owned three stores by the time he decided that his mechanical detail work could be used to invent a machine to slice bread. He sold the stores to finance his dream and got to work.

A prototype was destroyed in a fire in 1917, but ultimately, he completed his invention in 1927. Of course, to function, the machine required a loaf of bread with fairly specific dimensions; the bread had to sit in a cardboard tray at the end of the process.

The original loaves of pre-sliced bread were offered for sale by the Chillicothe Baking Company in Chillicothe, Missouri on July 7, 1928; the image is of the advertisement that ran in the newspaper the day before the first sales. By announcing sliced bread as “the greatest step forward in the baking industry since bread was wrapped,” the advertisement inadvertently gave rise to one of the most popular American idioms: “the greatest thing since sliced bread.”

Just as regular loaves made automated slicing easier, the regular-width slices made using a toaster much easier, and the sales of electric toasters went up dramatically. So did bread consumption, for that matter. Sliced bread became so popular that it caused a bit of a government snafu in 1943, when the Office of Price Administration banned the sale of sliced bread as a wartime conservation measure.

The ban was announced on January 18, 1943; here’s the reaction from the January 20, 1943 edition of The (Bend, Oregon) Bulletin:

|

Buyers Resent Order Banning Sliced Bread

There was a big beef going on in Bend today among housewives and restaurant owners but the beef was all about bread rather than meat. The beef grew out of the new OPA regulation prohibiting the sale of sliced bread, and according to a survey of local bakeries, “The women don’t like the idea.” To make matters worse, as soon as the present local stock of cutlery is exhausted there will be no more, due to a new government regulation to save steel. Some Bend firms report a run on knives since sliced bread went off the market. Size Varies

So, for a while at least, until housewives become accustomed to slicing their own bread again, little schoolboy Johnny’s lunch pail sandwich will probably appear thick one day and thin the next. The regulation was apparently made for several reasons–to cut the cost of cutting blades in bakeries, and to eliminate the inner wrapping, which heretofore has served as a “corset[“] to the slices. |

The prohibition lasted 49 days before being lifted on March 8 of the same year. A reaction to the lifting of the ban from the March 10, 1943 edition of The Pittsburgh Press:

|

Sliced Bread

It was a minor muddle, to be sure, but it seems too bad the government didn’t figure out before it ordered bakers to stop slicing bread that “the disadvantages” would “outweigh the advantages.” The few housewives who complained about the hardship of having to do their own slicing got little sympathy. Almost everyone was willing to make that sacrifice, if it would help to win the war. But what Secretary Wickard has discovered after nearly two months surely could have been learned much earlier by very little research. The bakers, already equipped with slicing machinery, would save no important amount of manpower or money by not slicing. They wouldn’t be helped out of the pinch between higher flour costs and fixed bread ceilings. And restaurants and other big eating places would need more equipment and more labor to do their own slicing. Anyway, pre-sliced bread is legal again. The question remaining is how many other Government orders have been issued without a weighing of disadvantages against advantages. |

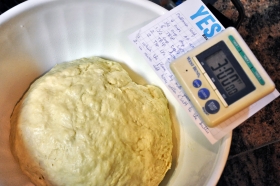

To make a proper Pullman loaf of your own, you’ll need a baking vessel with flat sides and a lid. The USA PAN we use in the pictures is made in the USA and sold at major kitchen retailers and online, but you could use a terrine, too. Other than that, the Pullman loaf is about basic techniques and patience, as all good bread recipes are.

And you should, at least once, taste a proper Pullman loaf. It has American progress in every slice. It’s like making a sandwich out of computers, telephones, NASA and the Internet, except with bread. Delicious, right? The Pullman loaf was the greatest thing leading up to sliced bread.

From Yesterdish’s recipe box.

Yesterdish’s Pullman Loaf

Pain de Mie

Pane in Cassetta

One 13 x 4 x 4 loaf.

2-1/4 tsp. active dry yeast, dissolved in 1/4 cup warm water

1-2/3 cup whole milk, scalded and cooled

4-3/4 cups all-purpose flour

2-1/2 tsp. kosher salt

6 Tbsp. cold unsalted butter cut in small cubes

Get your mixer, dough hook, large bowl, rolling pin and pastry scraper ready. Butter your Pullman pan.

- Mix the dough: pour milk, salt, yeast mixture [and flour] in the bowl of your mixer. Beat for a minute. Let rest for three minutes. Beat until a mass forms. Rest.

- Smash your butter and add slowly in pieces as the mixer runs on medium.

- You stop the mixer when the dough is sticky, elastic and with a nice sheen.

- Put in a clean buttered bowl for the first 3 hour rise. You are looking for it to triple.

- Deflate; turn the dough 3 times (envelope fold) and return for second rise — 2 hours.

- Pat the dough out. Fold on itself; seal edges to form loaf–smooth. Dough now gets placed in the pan–cover with plastic and let rise no more than 1 inch from top–30 minutes.

Preheat oven at 435 deg., lower middle rack–lid on the pan.

Bake 40 minutes–cool–serve!