Or pasta fasúl, depending on which part of Italy (or Jersey) you’re from.

Both pasta e fagioli and pasta fasúl mean pasta and beans; different Italian dialects have different words for the same thing (something we discussed previously in the post for Yesterdish’s avocado and goat cheese panzanella). Either way, it’s a peasant soup made with beans and pasta, and usually, some kind of ham.

Other than that, there isn’t a lot of orthodoxy about it. And my mother made this pot specifically to prove that point, after having to hear about how great some restaurant’s version was. (I’m not going to use the name, but you know the place. They brag about having a cooking school in Italy, then sell stuffed pastas that are entirely corporate inventions and are unrelated to any Italian tradition.)

It doesn’t matter that it’s made from the odds and ends of other meals–the leftover pork, the rind of the cheese, the last servings of pasta from the boxes. What matters in pasta e fagioli are the techniques and the time.

Of course, dressing up new recipes by claiming a nonexistent ethnic heritage isn’t anything new–we’ve talked about it with lobster Cantonese and chicken Kiev, among other places. But what happens with pasta e fagioli is something different–marketing gurus build a mystique around a dish that converts it from a natural expression of ingredients at hand to a bondage-and-discipline recipe that sends you to squint at the shelves in the specialty shop.

It doesn’t have to be that way, and it shouldn’t be that way. So let’s talk a little about the orthodoxy of pasta e fagioli.

First, some people will insist that pasta e fagioli must be made with cannellini beans, as if the cannellini was to pasta e fagioli what arborio and its short-grain cousins are to risotto. It’s not. Cannellini beans are basically just white kidney beans. There’s no “magical cannellini dust” that makes the soup part of a grand Italian tradition.

Peasants used cannellini when they had them, sure. But sometimes they used borlotti beans (the white-with-red-swirl beans that look like pinto beans), or regular kidney beans (particularly in Umbria), or whatever else they had at hand. You could even use lentils, although you’d have to omit the soaking period. We use an assortment of beans and the results are perfect.

Second, there’s a reputation in the domestic iterations that pasta fagioli is a vegetarian dish, because Jersey Catholics ate it on Fridays. While it’s true that a vegetarian bean soup would sometimes be used as a minestra di magro, or lean soup, on Fridays, it’s also true that pasta fagioli would be consumed during the rest of the week made with a meat stock, and usually, some pancetta or ham in the base. We used a triple stock, made by using a chicken stock that had been boiled until the volume reduced by half as the liquid in cooking down another set of chicken bones (you don’t need something that strong, but if you have it, why not use it?).

Third, the type of pasta. A lot of sources will say it has to be the tiny tubes called ditalini. To address this, here’s a story from my mother’s childhood in Eritrea, where her grandfather operated a general store.

In the store, short, dry pasta was sold in wooden barrels. To buy the pasta, you’d bring a clean pillowcase to the store, fill it with the pasta you wanted, and pay by the weight. (I asked if they factored in the weight of the pillowcase, but evidently, this wasn’t considered a big deal. You know that if they did this today, there’d be an old lady at the counter arguing that she wants her seven cents back.) When there wasn’t enough pasta to fill a barrel, it was moved into an odds-and-ends barrel.

If you were buying pasta for pasta e fagioli, that is the barrel you used to fill your pillowcase. As long as everything is relatively small with any larger bits broken into smaller ones, they’ll cook at about the same speed and make a soup that’s every bit as delicious and a visual improvement. This time, we used little shells, because that was the leftover pasta we had on hand.

Finally, the marketing drones have decided to popularize pasta e fagioli as a Tuscan bean soup. This would no doubt come as a surprise to the residents of Tuscany, who are fully aware that dishes of pasta and beans are common to Italian cities and former colonies the world over. I mean, it’s like advertising clam chowder as Kansas Clam Soup. Do they eat it in Kansas? Well, yeah, but that doesn’t make them the ambassadors of clam chowder.

Now, there is such a thing as a Tuscan bean soup; ribollita, made with cannellini beans, tomato, and kale, thickened with crumbled bread (which, in the authentic versions, wouldn’t be made with salt). Which is a lovely thing, but it’s not pasta e fagioli. And Tuscans do eat a lot of beans–they have a reputation as mangiafagioli. Along with ribollita, Tuscans enjoy their cannellini all’uccelletto (stewed with tomato, garlic, and sage) or al fiasco (that is, in a flask–cooked in a bottle and then served dressed with olive oil).

If you wanted to accurately describe the pasta e fagioli we typically eat in the United States, you’d call it a Neapolitan or Sicilian Bean Soup, because the thicker versions we enjoy are closest to Sicilian and Neapolitan pasta fasúl. But that’d never do for the big chain restaurants; Naples (which happens to be my favorite city in Italy, for the record) is rough and urban and Sicily is mostly associated with The Godfather. Meanwhile, Tuscany is all lovely rolling hills and olive groves and cottages (owned by rich foreigners, but you can’t tell that on the olive oil label).

While Italian immigrant communities brought the dish with them to the United States, it first started to catch on outside Italian communities during World War I, when the thrifty approach to cooking used by the poor in Italy was suddenly very useful to domestic households. Stretching one or two servings of pork into six or twelve servings of pasta e fagioli accomplished better popularity than any chain restaurant’s commercials.

It grew in popularity quickly enough to enter American pop culture in 1927, when vaudeville song and comedy duo Van and Schenck sang the praises of Pastafazoola (the sound is missing from some of the opening dialogue but it kicks in before the song):

That said, neither Van (born August Von Glahn) or Schenck (born Joseph Thuma Schenck) were of Italian extraction; both were born in Brooklyn and came from fully German ancestry. But growing up in Brooklyn, they had surely encountered a soup quite a bit like ours here, with a mixture of beans and whatever pasta was on hand that day.

It doesn’t matter that it’s made from the odds and ends of other meals–the leftover pork, the rind of the cheese, the last servings of pasta from the boxes. What matters in pasta e fagioli are the techniques and the time. With the right stock and properly soaked beans, the results will be creamy, rich, and warming–and often, more satisfying than the meals that contributed to its creation.

|

|

||||

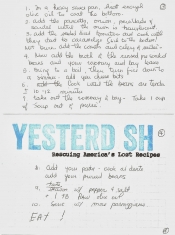

From Yesterdish’s recipe box.

Yesterdish’s Pasta e Fagioli

One medium diced yellow onion

2 charred, skinned, seeded, diced tomatoes

1 celery rib, diced

1 carrot, peeled and diced

1/2 to 1 cup diced pancetta or ham

1/2 cup diced Parmigiano rind

3 Tbsp. persillade (parsley and garlic)

8-10 cups of chicken/beef stock

1 spring rosemary

2 bay leaves

1/4 cup olive oil

salt

pepper *Grind fresh! No box!!!

1 cup of short pasta–ditalini or gemelli–whatever you like.

1 lb. = 2 cup soaked/brined rinsed beans–

Start cooking!

- In a heavy saucepan, heat enough olive oil to coat the bottom.

- Add the pancetta, onion, persillade and saute until the onion is translucent.

- Add the seeded diced tomatoes and cook until they start to caramelize and (stick to the bottom–not burn). Add the carrots and celery and sautee.

- Now add the broth and the rinsed, pre-soaked beans and your rosemary and bay leaves.

- Bring to a boil, then turn fire down to a simmer. Add your cheese bits.

- Cook until the beans are tender, about 10-12 minutes.

- Take out the rosemary and bay–take one cup of soup out and puree.

- Add your pasta–cook al dente. Add your pureed beans.

- Taste. Season with pepper and salt and 1 Tbsp. raw olive oil.

- Serve with more Parmigiano.

Eat!

Bean Brine:

1 lb. = 2 cups dry beans

3 Tbsp. salt

4 quarts of water

8-24 hour rest period. Soak at room temperature.

A brined dry bean that has been cooked properly will be creamy dreamy not mushy gluey!

Brining softens the skin only.