A recipe that calls for non-reactive cookware. (There’s a full-size version of the recipe here.)

|

Cast iron skillets, before seasoning (left) and after several years of use (right). Uploaded to Wikimedia Commons.

|

This will probably sound strange to people who were cooking in the 1960s and 1970s, because from the late 1980s onward, you really don’t encounter that much reactive cookware anymore.

So what is it? Well, imagine we want to cook a piece of salmon and we need to shop for a skillet. We want a pan that can conduct and hold heat well, so we can get a good color on our fish. We want something not too heavy, so we don’t break our arm using it. And we want something that won’t impart a flavor to the food.

Looking at metal alone–let’s ignore coatings for a moment–we’re only going to get two out of three of these things, tops. Stainless steel doesn’t react chemically with food and it’s not too heavy, but it’s a pretty lousy conductor of heat. Aluminum is extremely light and a conducts heat very well, but is highly reactive to acidic foods. (There’s a bunch of things that can go wrong with aluminium and acid, but the most common one is that acidic, salty food creates an aluminum salt that’s dark-colored and tastes like aluminum, although it’s basically not any more harmful for you than most baking powder.)

There are other, even more complicated options however. There’s copper, the best conductor of heat available in the kitchen aisle, but like aluminum, it’s reactive. Unlike aluminum, you can poison yourself by eating food that’s reacted with copper, if you eat enough of it. And then, of course, there’s cast iron–the almost-indestructible twenty-pound monsters that hold heat forever, but react with some kinds of food.

So what do you do? Well, fortunately, there’s more out there. Steel, cast iron, and aluminum all can be finished with an enamel coating, which is nonreactive and has a bit of a nonstick property to it (that is, enamel is less porous than metal, so the food sticks to it less). These days, most aluminum cookware is anodized, giving it a less-reactive exterior, though that property erodes over time.

For a long time, however, the state of the art was to put a disc of a highly-conductive metal, like copper, on the base of the pan, or to put a disc of aluminum there, then form the rest of the pan out of steel. Steel’s non-reactive, easy-to-clean cooking surface combined with aluminum’s heat distribution made a fantastic pan–the only down side was that the edges of the pan cooked food differently than the bottom.

That was the state of the art until the 1970s. In the 1960s, John Ulam worked to make bonded metals for things like coins and rockets. Understanding the dilemma of reactive and non-reactive metals (that the best conductors are the worst cooking surfaces), he formed pure aluminum, aluminum alloys, and stainless steel into a sheet, then formed the entire pan out of the bonded sheet, so the conductive metal core extended through to the edge of the pan.

In 1971, Ulam formed All-Clad, which uses this process today to make its well-respected pans. There are even “upgraded” lines using copper cores and more alloys, although I’ve never met the All-Clad I didn’t love.

That said, when we’re talking about crawfish (I used to call them crayfish, too, until I tasted one, and then I realized they taste like a crawfish more than a crayfish), I’d be remiss if I didn’t say that seasoned cast iron is all but non-reactive. Seasoning is a process of heating layers of oil on the pan until the oil polymerizes and creates a non-stick, rust-resistant protective coating. That, combined with cast iron’s heft and indestructibility, means a properly seasoned, properly maintained cast iron pan will last more or less forever.

I have two hanging in my pantry that my mother gave me. If I ever have great-grandchildren, they’ll have the same ones, I expect.

From a box sold in Martinez, California.

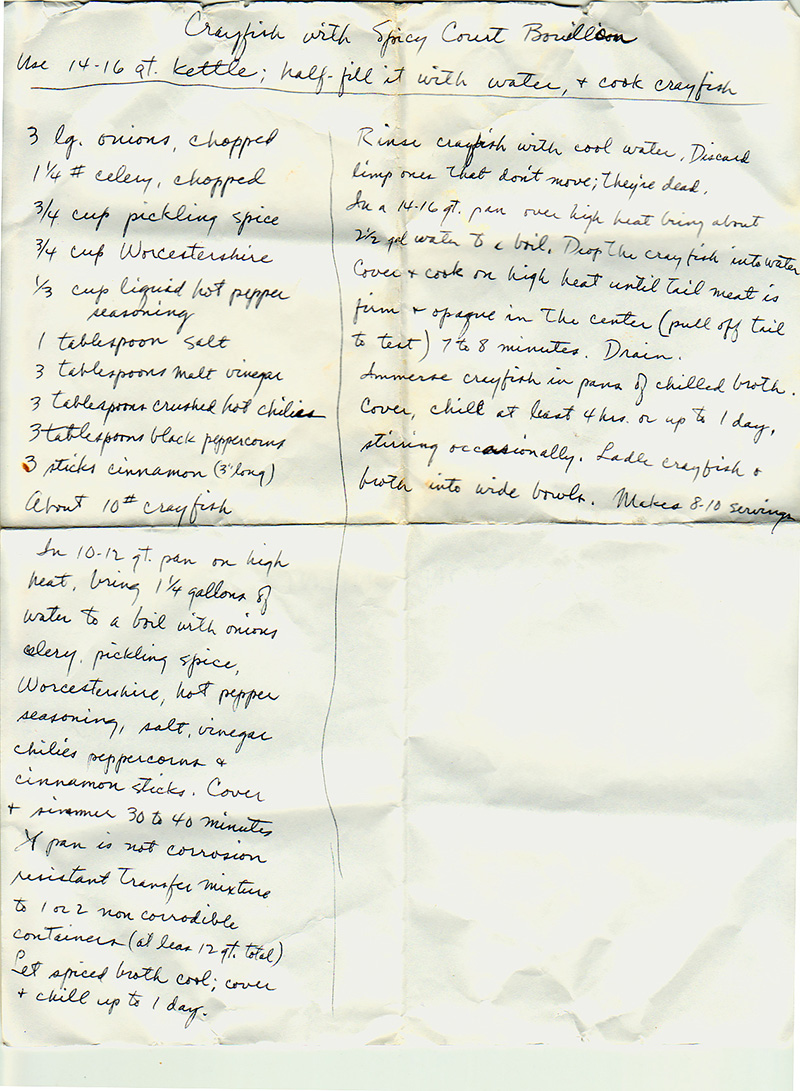

Crayfish with Spicy Court Bouillon

Use 14-16 qt. kettle; half-full it with water and cook crayfish.

3 large onions, chopped

1-1/4 lb. celery, chopped

3/4 cup pickling spice

3/4 cup Worcestershire

1/3 cup liquid hot pepper seasoning

1 Tablespoon salt

3 Tablespoons malt vinegar

3 Tablespoons crushed hot chiles

3 Tablespoons black peppercorns

3 sticks cinnamon (3″ long)

About 10 lb. crayfish

In 10-12 qt. pan on high heat, bring 1-1/4 gallons of water to a boil with onions, celery, pickling spice, Worcestershire, hot pepper seasoning, salt, vinegar, chiles, peppercorns and cinnamon sticks. Cover and simmer 30 to 40 minutes.

If pan is not corrosion resistant, transfer mixture to 1 or 2 non-corrodible containers (at least 12 qt. total).

Let spiced broth cool; cover and chill up to one day.

Rinse crayfish with cool water. Discard limp ones that don’t move; they’re dead.

In a 14-16 qt. pan over high heat, bring about 2-1/2 gallons of water to a boil. Drop the crayfish into water. Cover and cook on high heat until tail meat is firm and opaque in the center (pull off tail to test) 7 to 8 minutes. Drain.

Immerse crayfish in pans of chilled broth. Cover, chill at least 4 hours or up to 1 day, stirring occasionally. Ladle crayfish broth into wide bowls.

Makes 8 to 10 servings.