A down-home style preparation of a soul food classic.

Oh, believe me, there are upscale versions of fried okra. I’ve seen them scored, par-boiled, dredged in lentil flour and batter-fried. I’ve seen them bacon-wrapped and oven-fried.

Even now I’m working on a plan involving smoked duck fat. (Which you may see here at some point.) And it’s all delicious and I’m in favor of all of it.

But today? Today, we’re not talking about that kind of fried okra.

The best advice on making fried okra is to make twice as much as you want to serve, because half of what you make is going to get eaten up before it leaves the kitchen.

Today we’re talking about about what you get when you go to an Oklahoma barbecue shack and order one of the four things on the menu that isn’t meat. Or getting a restaurant recommendation from the guy who runs the hardware store in a small town in Texas and the only words you can make out are “fried okra.”

Or visiting a Louisiana kitchen where new food is making it to the table every two minutes and the fried okra never makes it off the kitchen counter because people stand right there and eat it up. That’s the best way, if you’ve got a friend who makes okra and doesn’t whack you with the spoon for trying.

Fried okra was never a recipe designed to be particularly formal. In fact, there aren’t many 19th century recipes for fried okra as we’d understand it.

Which is what you’d expect, really. Soul Food consists of contributions from primarily two sources. One, the Native American tribes who lived in the south and communicated with enslaved black people, and two, enslaved black people themselves.

For the most part, tribal languages didn’t have written forms. The Cherokee were the exception; in 1821, Sequoyah completed the 85-character Tsalagi Alphabet. While it had more characters to learn, once learned, they could be combined into words more rapidly, and thousands of Cherokee were literate within a few years. The Tsalagi word for okra transliterates to something like kawi uliyoda (it’s a tonal language, so the inflection would matter).

A complicating factor in looking for Cherokee recipes is the Trail of Tears. After 1838, many Cherokee were learning recipes for the new crops where they were, and what recorded recipes we have show strong influence from interactions with enslaved blacks. By the 1830s, enslaved blacks, who had been permitted to read but not to write in most Southern states, were denied education altogether in the crackdown after Nat Turner’s rebellion.

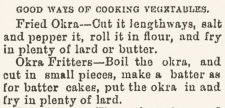

Under those circumstances, it’s not strictly shocking that we don’t see much in the way of fried okra recipes until the last third of the 19th century, like these okra recipes from the November 8, 1895 edition of the New Oxford (Pennsylvania) Item:

|

Good Ways of Cooking Vegetables.

Fried Okra–Cut it lengthways, salt and pepper it, roll it in flour, and fry in plenty of lard or butter. Okra Fritters–Boil the okra, and cut in small pieces, bake a batter as if for batter cakes, put the okra in and fry in plenty of lard. |

As we’ve discussed before in the post for Yesterdish’s Gumbo for a Crowd, okra itself came to the U.S. from Africa, likely on slave ships. Frederick Douglass observed in 1845 that the monthly food provided to an enslaved person was “eight pounds of pork, or its equivalent in fish, and one bushel of corn meal.” So it’s not too hard to imagine that, with cornmeal and okra, fried okra appeared more than once at the table in the Old South.

It wasn’t really until the late 1950s and early 1960s that soul food as a category entered the public consciousness as a positive thing. Soul music came along first, actually, connecting then-contemporary rhythm and blues to the gospel style of Southern churches:

Prior to soul music, the phrase “soul food” meant church or religion, and recipes like fried okra were “down home cooking.” But some collective subconscious cultural re-branding brought fried okra (and chicken, and greens, and corn pudding and the rest) under the Soul Food umbrella.

With the new category came a new respect. It was no longer about necessity, but about connecting to traditions; about recognizing that okra doesn’t have anything to apologize for. When done right, country fried okra is golden, crisp, and rich, the spice and salt tempered by the fresh texture.

The best advice on making fried okra, handed down by generations of cooks, is to make twice as much as you want to serve, because half of what you make is going to get eaten up before it leaves the kitchen. Ignore this wisdom at your own peril. In taking the pictures, the supply of okra steadily diminished.

From Yesterdish’s recipe box.

Yeserdish’s Fried Okra (Country Style)

Approximately, because who measures?

- About 1 lb. okra, washed and cut into 3/4 inch sections

- About 1.5 cups cornmeal

- About 1.5 Tbsp. flour

- About 2 tsp. each salt, pepper, cayenne

- Buttermilk

Mix cornmeal, flour, and seasonings. Coat okra with buttermilk, then toss in dredge, repeating if necessary.

Fry over medium high in vegetable oil.